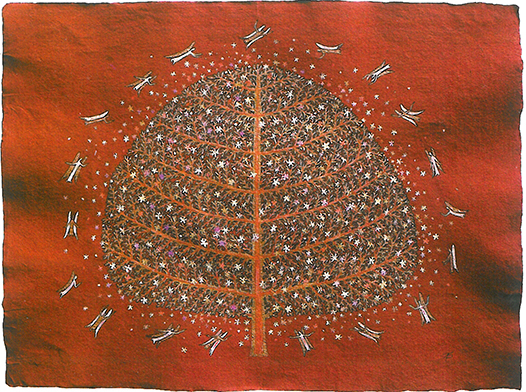

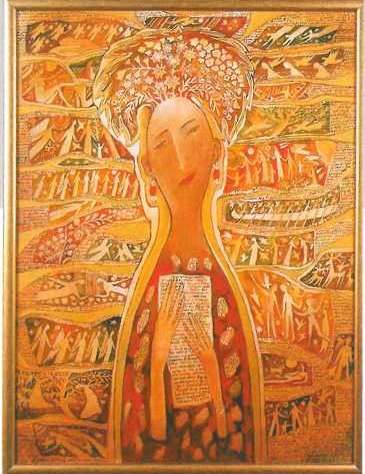

Paradise Tree

by LIDIYA BORYSENKO

Lidiya Borysenko was originally destined to become a musician, but, as they say, nature took its course: in a family where both her father and older sister were artists, it was almost inevitable that she would follow in their footsteps. However, she chose her current profession without the slightest pressure from them. Borysenko has no regrets—especially since music “resonates” in each of her compositions. Her works have been featured in numerous international exhibitions in Ukraine and abroad and are part of private collections in her home country, as well as in Germany, the United Kingdom, Finland, Belgium, and the United States.

So, Lidiya, would you share your “recipe” for becoming an artist?

My story isn’t unique—it simply proves the obvious: when creativity fills a home, it’s impossible not to be “infected” by it. Everything around me influenced my decision to pursue art as my life’s calling: my native Lviv with its ancient architecture, the magical works created in my father’s studio—he was the renowned sculptor Valentyn Borysenko—my sister Natalia’s textile art, and her husband, the sculptor Mykola Bilyk. My mother has always been very artistic—she recited poetry and sang beautifully for as long as I can remember. My grandfather was a master puppeteer, and my grandmother, with her delicate white lacework, was my first textile teacher. When our family moved to Kyiv (my father became head of the Kyiv Art Institute and taught there), I transferred from the Lysenko Music School to the Shevchenko State Art High School, where I entered the painting department. After graduating, I became a student at the Lviv Institute of Applied and Decorative Arts, majoring in textile art. I was lucky to study under wonderful teachers, including my uncle, the renowned painter Volodymyr Sydoruk, as well as other celebrated artists such as Viktor Zaretsky, Borys Lytovchenko, Yevhen Kotsiuba, and Ihor Bodnar.

And I read a lot. Fairy tales had a huge impact on the development of my own visual language. I still return to them today—they hold deep meaning and subtext. Since the age of 12, my favorite book has been The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Beyond his writing, it was his drawings that helped me fall in love with and truly feel the power of the line.

In short, read always, read everywhere…

Yes, I was practically programmed to read—by my father. He was creating bas-reliefs for the facade of the Ukrainian House, which at the time was the Lenin Museum. And on one of those reliefs, he depicted his loved ones. Me, in particular—holding a book that read: “Study, study, study!” As you can imagine, I really didn’t have much of a choice!

By the way, there’s quite a story behind that bas-relief. A friend of mine was almost taken to the police: she saw me on it and burst out laughing (well, kids will be kids), and this happened right under the walls of the Lenin Museum!…

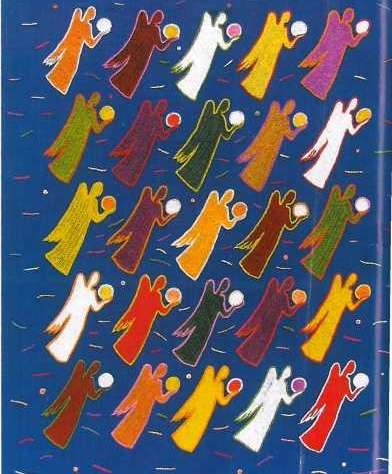

From the series “Paradise Trees”

Handmade paper, colored ink, 75×55, 2006

No matter how much you shy away from the word “unique,” it directly applies to you: today, Lidiya Borisenko works in eight techniques! Is this a step toward the Guinness Book of Records, or…?

Creativity is the pursuit of truth. To me, it’s a crystal with many facets. Likewise, techniques are the facets that, to some extent, reflect my understanding and perception of the world. Yes, right now my interests include painting, graphics, levkas, tapestry, embroidery, pysanka, batik, and collage — but I’m certain I won’t stop there.

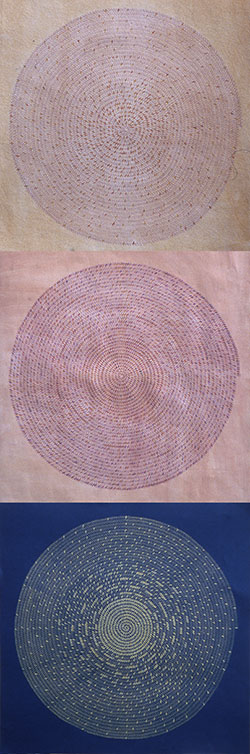

“Circles” Handmade paper, colored ink, 30×30, 2006

“Circles” Handmade paper, colored ink, 30×30, 2006

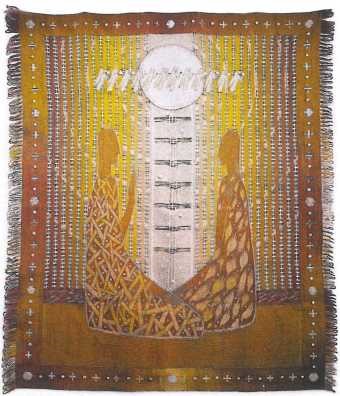

Creating a tapestry can take a year—or even longer. I have several large-scale ones, 2 to 3 meters wide. These are serious, monumental works. Take “Mind and Heart,” for example: an original technique, textile with backlighting, which represented Ukraine at one of the most prestigious international textile biennials in Łódź, Poland, in 1998. I’ve also created works in embroidery—an even more meticulous technique than tapestry. Several of them were awarded diplomas at the Kyiv Textile Triennale. While large works of this scale—demanding in time, materials, and composition—are in progress, I also create in other techniques. Graphics, for instance, feel like an extension of textile: the pen becomes a needle, the line a thread. Levkas gives a material richness and archaic weight to my graphic images. Collage, like levkas, shifts form and texture, breaking the boundary of the square. Painting on silk (batik) is a play of light and lightness. Fabric is the easiest medium to move through space—my exhibition “Translucent Graphics” was shown in Switzerland. Then there’s pysanka—Ukrainian ritual egg painting. I studied its symbolism independently and learned the technique from a real Hutsul woman, a hereditary master. The pysanka’s symbolic language and cosmology led me down a path toward understanding ornament as a whole. By the way, I’ve painted over 2,000 of them so far.

“The Four Elements”

Pysanka (ostrich egg), 2007

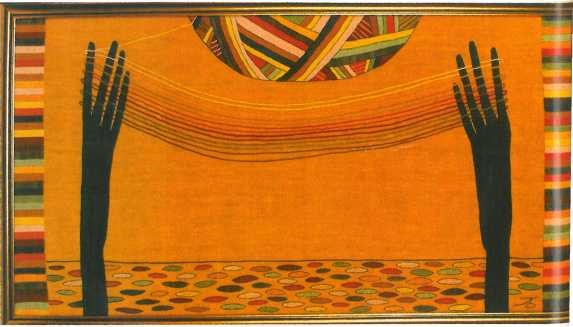

“Mind and Heart”

Tapestry, original technique, wool, cord, silk. 260×290, 1998

And among them — something as exotic as ostrich eggs?

With the emergence of ostrich farms in our country, they’ve become quite accessible. Still, an egg is an egg. The large size of the ostrich egg allows it to be viewed as a sculptural object, and its texture closely resembles ceramics.

Finally, the 8th technique is painting — though it clearly reveals a post-embroidery syndrome. My first painting, “The Letter,” was inspired — as it should be — by a muse, who, in this case, appeared in the form of a former classmate. Years ago, he moved to the U.S. and became a successful artist. Then one day, I received a letter from him — a beautifully written confession that he’d been secretly in love with me back in school. After reading it, flowers bloomed on my head… — in the painting!

“Journey”

Hand embroidery, linen cotton, 60×90, 2004

One wants to look at your images for a long time and unravel their meanings, “trying them on” different contexts. The only thing one can say with complete confidence is this: they are all spiritual. Just like your works as a whole.

“Return to the Thread”

Hand embroidery, linen cotton, 110×45, 2005

Surprisingly, these images are embraced as “their own” by followers of various faiths — Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, Sufism, Vedic culture… My images are symbols of the absolutely real world. I clearly understand that everything I depict is alive and has its purpose: the harmony of Heaven and Earth within a person, tuning the soul to a higher pitch. These are ancient images, modernized and materialized through me. They are meant to bring joy (my recent project with the wonderful ceramic artist Nelly Isupova was called “Rado” — meaning “Joy”), which is why I call them art therapy. Judge for yourself: recently a businessman from Moscow called and shared that whenever his little child starts crying, they can soothe him simply by showing my works.

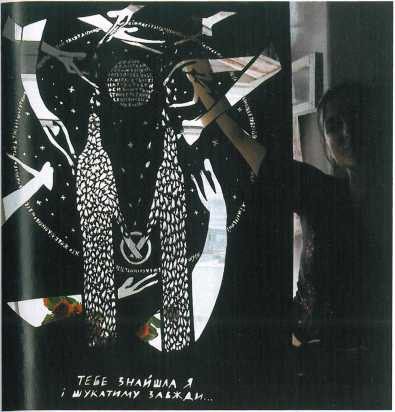

“Two”

Vytynanka (paper cutting), cardboard, ink, pen, 50×70, 2000

Every artist has favorite images. Of course, I do too, and among them is the Paradise Tree. The worship of trees is a very ancient ritual. Trees were identified with both the person and the family. So, the Paradise Tree is what we must revive on Earth, because the Earth is Paradise — currently somewhat lost, but truly capable of being reborn.

“The Fish That Loves to Listen to Beethoven’s Music”

Levkas (gesso), wood, 90×50, 2007

The images are children of a single informational field. I became convinced of this through a concrete example. One night, I dreamed of “hints” for future compositions.

And like many women, I have a lot of problems: going to the housing office, the market, dealing with issues related to my daughters’ education… In short, no time for them. So, one day I’m walking through the Artists’ House hall and see two men looking through a portfolio—and there are images I hadn’t had time to bring to life! So, they went to others.

How do you define your art — symbolism?

You could say that, although I feel closer to social realism, the realism of our time.

I perceive my works as living beings; they behave accordingly — each with its own moods and destinies. Some, for example, find their owners right after coming into the world, others only after traveling through many exhibitions, and some remain in the studio. Even after being exhibited, they are different, but most often — tired…

Which of your works are the most beloved and meaningful to you?

My daughters. They are creative souls as well and in every way much better than me. I suppose it should be that way. What they enjoy doing is music (they are laureates of music competitions), painting, graphics, and poetry. Yaryna and Olga are my best friends and… teachers.

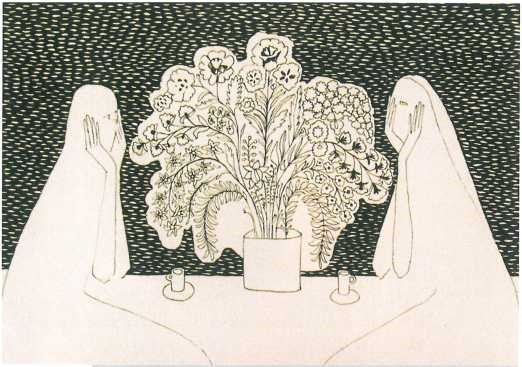

From the series “Two”

Paper, ink, pen, 30×21, 2004

You inherited another profession as well, didn’t you?

Yes, I teach, like absolutely everyone in my family. My audience is children; currently, I teach at an art studio under the Union of Artists of Ukraine. I am sure nothing in life is accidental. I was born on International Children’s Day, and under the guise of a teacher, I come to learn from them—or rather, to learn together—for almost 10 years now. This helps me in my work. Children’s creativity is truly special, and, in my opinion, representatives of other art forms should learn from it, if only because it comes from the land where we all originate—from Childhood.

Text: Iryna Zhenko

Photo: Oleksandr Yalovyi

From Lidiya Borysenko’s personal archive

“Letter”

Canvas, oil, 85×65, 2004