Kost MOSKALETS

UNWRITTEN LAWS OF THE PYSANKA

This world order, the same for all, was not created by any god or man, but it always was, is, and will be—an ever-living fire, kindling in measure and going out in measure.

Heraclitus of Ephesus

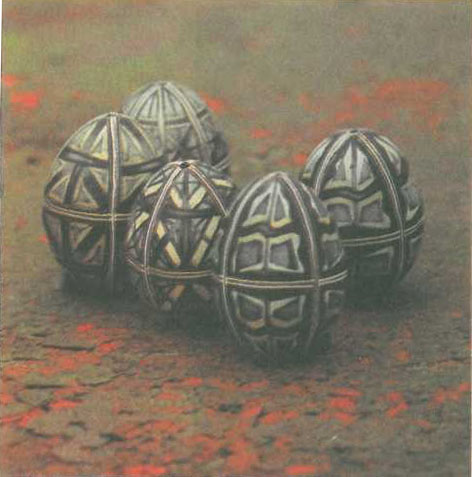

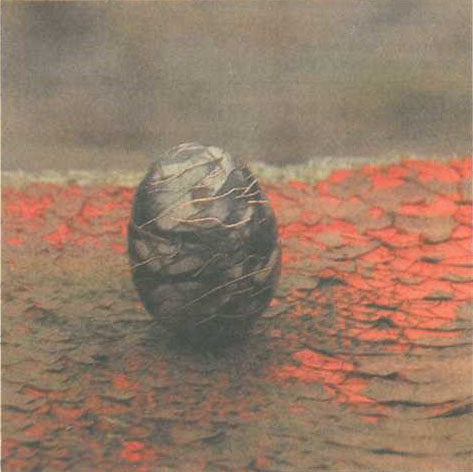

The paintings and pysanky, the reproductions of which you see on the pages of this magazine, no longer exist. They remain only in photographs — the result of more than a year and a half of painstaking work by Lida Borysenko and Andriy Sayenko. These paintings and pysanky cannot be bought or sold for any currency in the world — and that is the most compelling proof of their eternal value. These works have turned to fire, smoke, and ash, having forever departed to that place where a snow-covered paradise exists, where burned-down barns and crickets settle once again — to sing, or to remain silent. Let us carefully look at what remains in the photographs; and I will try to explain what exactly happened on August 1, 1992, in the studio of the young couple.

It began with long years of apprenticeship. There were brief but passionate fascinations — from cityscapes in the style of Utrillo or Bonnard to portraiture. There was a nostalgia for the Impressionist purity and sincerity of vision. There was the avant-garde. And there was the Lviv Institute of Applied Arts. But all of it rather quickly gave way to boredom and disappointment. For an artist is truly authentic only when walking a path untrodden by others before them. All other roads, no matter how wide or attractive they may seem, ultimately prove to be mere detours leading to the abyss of imitation and epigonism.

Freedom and solitude, authenticity to oneself — these are the alpha and omega of the artist, if they are truly human.

Freedom is one of those sources of human existence, the repression or unrealization of which brings catastrophic consequences to the individual. That is why the search for freedom outside oneself is doomed from the start. But this does not mean that the search for freedom within is guaranteed to succeed. For to search within, one must fully be oneself; and to fully be oneself, one must be free.

This tragic paradox is the fate of the human being throughout the entirety of their existence.

One of the ways to comprehend this paradox is through creativity. To comprehend does not mean to answer the question posed to us by existence; to comprehend means to hear that question and to truly understand its essence — because it is the essence not simply of human existence in general (!), but the most immediate, most authentic part of myself, of my fate here, the essence of my life and my death.

I cannot answer this question, if only because the question — is myself. I am here, in this question. And at the same time, this question is not the whole of me. In order to answer it more or less satisfactorily — that is, completely and perfectly — one would have to go beyond the limits of one’s own “self,” beyond one’s own fate, and beyond the limits of the question itself. And we know well that under the conditions of our existence, such a step is not possible. That is why this question, which each of us must hear and understand in its essence, is not only about my fate here, not only essential to my life, but also essential to my death. Because it is death that constitutes the departure from the boundaries of “my self here,” and thus it is the only real opportunity not just to seek a true understanding of the question, but to seek a true and meaningful answer to it. I want to emphasize that it is death itself — and not what may or may not come after it — that stands as our only (ultimate) real evidence of the possibility of stepping beyond a form of being constructed as a question, whose ongoing existence is nourished by human freedom and self-identity.

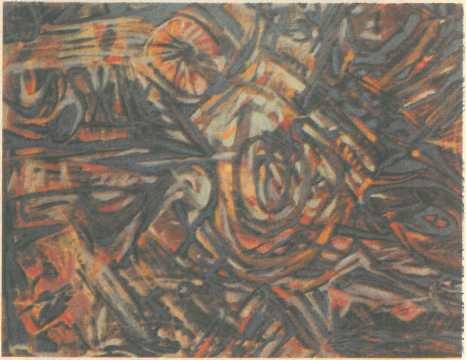

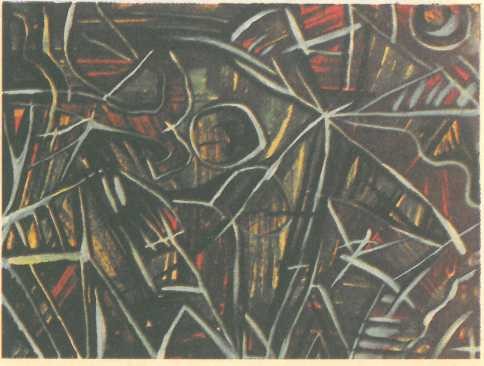

Andriy Sayenko was more inclined toward risky searches and abrupt stylistic turns; this is reflected in the intense color and dynamic quality of most of his early paintings. He asked himself questions — and that was the most innocent of pursuits. However, it was Lida Borysenko who first began painting pysanky.

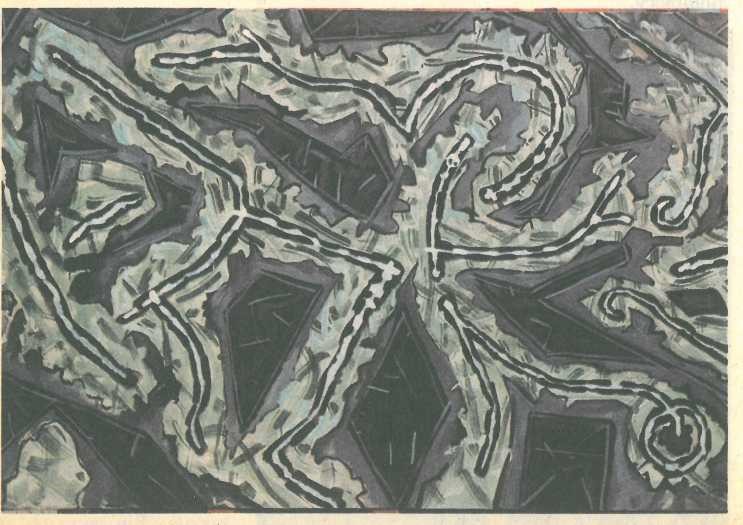

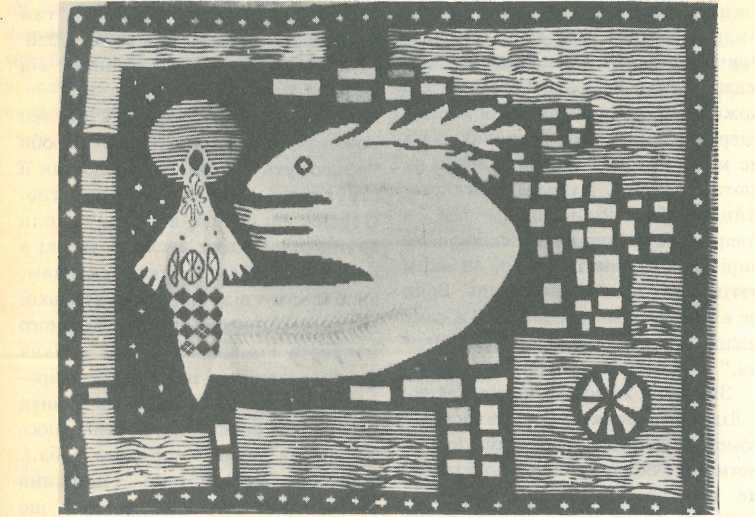

The pysanka is an image-symbol, a concept and at the same time the meaning of that concept. The polysemy of the pysanka is the result of centuries of layered meanings imposed upon the egg — and within it — as a symbol of the universe, of wholeness, of eternity. At the same time, it carries a multitude of meanings encoded in the ornamentation of the pysanka: in the profound significance of its wavy lines, dots, colors, crossings, and interwoven geometric figures. The pysanka is so named precisely because it is a form of writing — a means of transmitting meaning — a symbol of symbols.

It is understandable that, at first, neither Lida nor Andriy fully realized this. They were simply intrigued by a new material, a new form of expression.

The comprehension of what they had encountered came much later — when there arose a need to uncover the primary idea embedded in the painted noumenon and to express it. That marked the beginning of library searches and the study of works dedicated to symbols and symbolism, particularly ornamentation. It became clear that ornamentation is saturated with meaning, that it cries out to us with countless messages — but we have forgotten its language. “As we attempt to interpret the meaning of the complex and mysterious compositions of Trypillian painting, we are entitled to view them not as a senseless collection of ornamental elements, but as a system of views of an ancient artist, expressed through the combination of numerous pictograms.”

— (B. Rybakov, The Paganism of Ancient Slavs).

So then — symbolic painting?

And the day came when they realized they could read. And more than that — they understood that they themselves had something to say in this ancient language. From that moment on, neither Andriy nor Lida created traditional pysanky intended for sale.

Selling — that was tradition. But what they had begun to write was no longer traditional. Using the ancient language, they started to express a new meaning — one grasped by artists born after Picasso, Dalí, and Mondrian. But they didn’t yet know that this was only the beginning — and that ahead lay another, more powerful and significant transformation of style, which would bring — understanding? revelation?

That symbolic painting is not limited to the pysanka alone — I believe that conscious revelation came to them the moment they stood before the remains of their workshop, completely destroyed by fire, and looked at what was left of the tapestry woven by Lida Borysenko. The tapestry had been stretched on a wooden frame with backlighting and was meant to be viewed at night. Unfortunately, no slides or photographs of this tapestry — the result of months of spiritual and manual labor — have survived.

So, when they stood before the charred wooden frame, where just a day before a monumental tapestry had lived, a moment of revelation came — a moment of unprecedented silence — and in that silence, they heard and saw: the burned wooden frame, the shattered shells of decorated pysanky, soot and ash, the charred pages of Ivan Malkovych’s poetry collection The Key, easels, canvases, frames, brushes, paints, completed and unfinished works — all destroyed by the fiery element — and yet, everything continued to speak to them and resonate with meaning. It continued to signify, to speak a language more restrained, refined, and authentic. And in that moment, they realized that they were standing before the true reality of freedom — that they had finally awakened. It was not only the first performance of their lives but also the last dream of their student journey.

The longing for vision has vanished. The vision remains.

Why search for vision, if it comes at such — or even a higher — cost? Why search for freedom? In order to fully be oneself? In order to be free. Let us pause briefly and recall the fate of the Ukrainian poet and painter Taras Shevchenko, who, among other things, gave us the brilliant comparison: “The village looks like a pysanka.” His life clearly follows a distinct structure: birth — bondage — freedom — bondage — freedom — death. In order for the young serf Shevchenko to realize his extraordinary artistic talent, he was ransomed from bondage. Formally, he gained his freedom at the same time as he discovered the first traces of his identity as an artist. Yet in essence, he remained a captive — because the freedom granted to him was not yet truly his own, not innate like his artistic gift. It was a freedom found outside of himself and not recognized as such. But the ransom from bondage was already a powerful push toward the search within. Without yet knowing what he was looking for, Shevchenko began to write his first romantic ballads in the folk style.

What does it mean — to fully search for one’s own identity? Or to search for one’s own authentic freedom (not one seemingly imposed from outside)? Or both at the same time? After all, being ransomed from bondage is itself a form of humiliation and still carries slavery within it. Shevchenko needed to become both free and himself. He joined the Kyrylo-Methodius Brotherhood, wrote “The Dream”, and prepared to move from Petersburg to Kyiv. His last free days in Borzna were free in every sense — both formally and essentially. Before us are the deliberate and free acts of a person who has already formed and created himself — and created himself free.

During the crossing over the Dnipro River, Shevchenko was arrested. Ahead lay a long exile in a foreign land. Ahead lay bondage. An absurdity, if you think about it — for Shevchenko’s bondage was already behind him. But time ignores any linear notions of itself. Shevchenko once again falls into bondage. Bondage is the same dimension of time. But here is what is extremely important: it is not the same Shevchenko who falls into bondage. This Shevchenko will never forget the location of the source of freedom within himself — this toponymy and phenomenology were painfully clear to him. Returning from exile, Shevchenko quickly fades away. Yet his poems from this period are the most profound…

[The text references a book cover with the word “Key”. Maybe this was how the fire wanted to justify itself, to show what it leaves behind, and hint at the purpose of its coming — the Key.]

…and the third egg I carried for seven days under my armpit: seven times around the house by the northern full moon, and at dawn I threw it lengthwise through the house, and when it fell to the ground and cracked in two — a multitude of dark brown-eyed beasts began to crawl out of it…

(I. Malkovych, “The Forerunner”).

Honestly, I don’t even know what matters more to me here: the theme of pysanky and their inexhaustible symbolism—or the theme of the fire in which they burned, a fire equally inexhaustibly meaningful. They had become so inseparably intertwined and fused into one that looking at these photos and slides you feel an involuntary fear; something like what the owner of a small collection of ball lightning would feel.

Two weeks after the fire, Andriy Sayenko and I were sitting in his kitchen smoking hand-rolled tobacco; outside the window raged an August thunderstorm. Andriy was telling me about possible causes of the fire. One theory came from the poet Vasyl Herasymiuk: the fire happened because of the accumulation of energies in the pysanky and paintings; they had no outlet, and something like an explosion occurred. Ball lightning. Egg-shaped lightning. Andriy and I exchanged glances and unanimously decided to close the window, behind which a whole key of lightning bolts was flying. They don’t strike the same place twice, but… “Everything is ruled by lightning,” says the old Heraclitus.

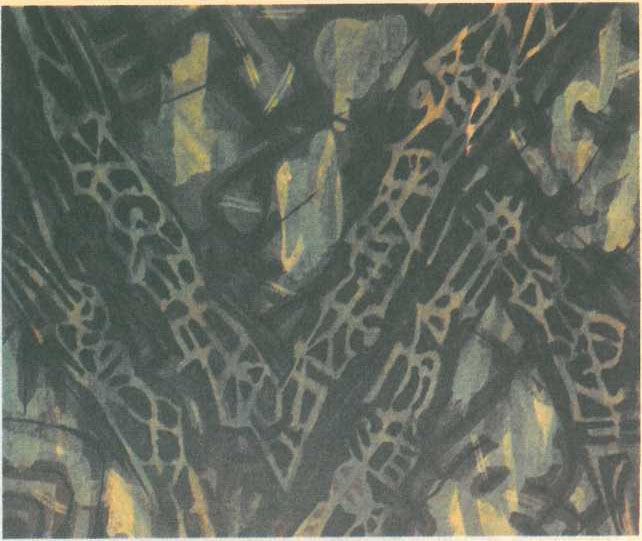

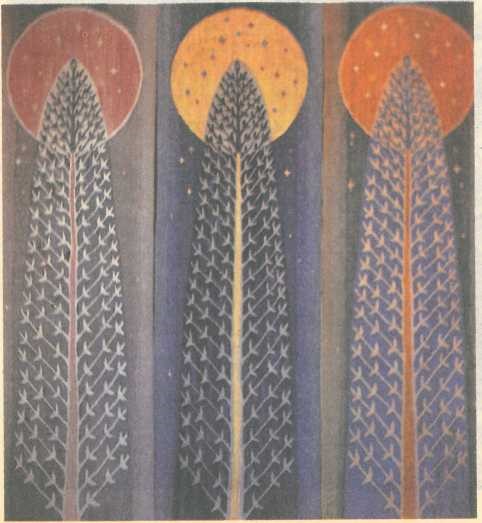

The symbolic painting of Andriy Sayenko and Lida Borisenko is not mimetic painting; it must be read like musical notes, or rather — seen with the eyes as if hearing, because it is a kind of music. Sometimes these pysanky resemble stained glass windows; one only needs to understand that the sun does not rise outside of them, but within them, radiating to us ornaments and countless ways of seeing and understanding them. Hokusai painted one hundred views of Mount Fuji, intuitively following the principle of complementarity later formulated by Niels Bohr (we can also recall similar attempts by Cézanne and Claude Monet). One hundred views of the same mountain (Fuji or Saint-Victoire…), illuminated by the same sun. Each pysanka by Lida and Andriy is a separate mountain and a distinct sun, small models of universes, different each time.

Is there something that unites them into a single visual environment, fusing them into a whole? Yes; and this one unifying element is fire.

“After such a thought, artists will start burning their studios with their own hands,” — Andriy Sayenko remarks melancholically.

The multiplicity of ornaments is balanced by the unity of the form on which they are arranged — the unity of the egg. By eliminating visible lines and colors, we return to what remains invisible beneath their layer — to the pure essence. “Everything visible is dead, and the more visible it is, the more dead it is,” says Hryhoriy Chubay. “The invisible harmony is stronger than the visible,” says Heraclitus.

A year before the fire, Andriy Sayenko began making conceptual attempts to “undress” the pysanka, transferring its structural components onto canvas. The first thing that comes to mind when seeing the results of these experiments (some of which have been preserved thanks to slides taken during Sayenko’s exhibition in Munich at the gallery of the renowned patron Roman Schuper) is their fragmentary nature and the insufficiency of space. Essentially, it is hard even to imagine the necessary size of these paintings: something like snapshots of a starry sky… It is quite natural that the canvas surface turns out to be too confined for what was fully contained on an ordinary egg. Despite their modernity, lack of frames, and interesting twists in the artistic logic typical of working on canvas, these paintings somehow strangely resemble skins torn from some unseen creatures… Don’t we feel a similar impression when we see the pelts of valuable animals, no matter how beautiful those pelts are on their own? More convincing are the attempts in which the painter abstracts from ornamental connotations, capturing not their visible form-expression, but the invisible essence, drawing from different waters flowing through the same channels. Not reproducing the arrangement of lines of ancient riverbeds, but opening new sources of living water that will carve their own paths — this roughly defines the essence of Andriy Sayenko’s current works.

And that is precisely why, at the beginning of these notes, I mentioned the performance. To “undress” or “disassemble” the pysanka, to try to unfold it on a flat surface, is quite a risky endeavor. At the same time, one can understand the young artists for whom being confined to a once happily found form would be a form of creative suicide and enslavement. Personally, I eagerly await the expressions of creative movement from Lida Borysenko and Andriy Sayenko within the space of freedom they are creating. The charred wooden frame, on which the luxurious, almost unseen tapestry was stretched, will become one of the important symbols of something that has not existed before — the genuine authenticity of an artistic work.

But what about the pysankas, their laws, freedom, authenticity, and everything else? “In exchange for fire — everything, and for everything — fire, just as goods are exchanged for gold, and gold for goods,” says the old Heraclitus.

*A similar monologue can be found in E. Ionesco’s Délire à deux:

“He, … I was asking myself questions. I had to answer the questions. What question was I asking myself? I don’t remember. But to get an answer, I had to ask myself a question… A question. How can you get an answer if the question hasn’t been asked? So I kept asking questions, no matter what; I didn’t know what the question was, but I still asked it. It was the most innocent activity. The one who knows the question is a trickster… Let us ask ourselves: does the answer depend on the question, or does the question depend on the answer? That’s another question. No, it’s the same one…”